Marie Moyer

COLUMBIA, Mo. (KMIZ)

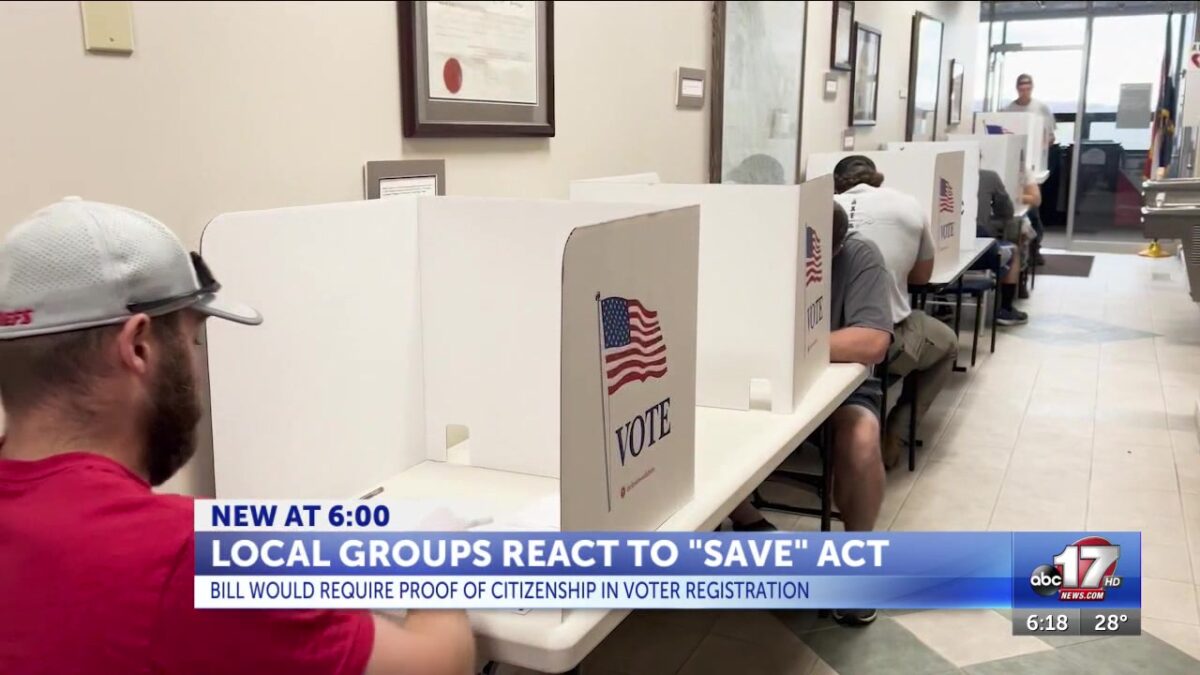

With the U.S. Senate reviewing House amendments in the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act, the bill needs Senate approval to be moved to President Donald Trump’s desk.

If approved, the SAVE Act would require those registering to vote to have proof of citizenship. Supporters argue the bill strengthens election integrity, while opponents argue it adds unnecessary bureaucracy to the voting process and disenfranchises eligible voters.

Sen. John Hawley (R-MO) praised the bill in a statement.

“We ought to pass the SAVE Act,” Hawley said. “I think we ought to have it nationwide. We ought to make national elections safe and secure and fair, and the best way to restore confidence in our national elections is to pass these commonsense rules.”

It is currently illegal for non-citizens to cast ballots, with applicants required to self-report their citizenship in applications. Current safeguards also compare registrations with data from the Social Security Administration, the Department of Health, Department of Revenue and sometimes the Department of Corrections.

The SAVE Act also applies to those re-registering to vote after moving or changing their name.

Valid documents to prove citizenship include a passport, a birth certificate and military identification cards.

“It’s checking for eligibility on a variety of areas on the voter registration form,” Boone County Clerk Brianna Lennon said. “When we’re looking at the voter registration application that comes in, the voter checks off that they are a citizen and then they’re also attesting under penalty of law that they are a citizen.”

Opponents claim citizens would be affected by the bill.

“Senior citizens whose IDs may be expired, voters with disabilities who may not drive, young people who may move frequently, low-income and low-wage workers who may not have the fees necessary to get those underlying documents because they’re not free,” said Denise Lieberman, who is the director and general counsel of the Missouri Voter Protection Coalition.

Lieberman added that citizens with out-of-state birth records, records with possible errors and victims of natural disasters also may run into issues with accessing valid documents.

“These measures would simply impose additional burdens on the voters themselves, United States citizens who have a fundamental right to participate and make them prove they are a citizen, even though they’ve already proved they are who they say they are,” Lieberman said.

Critics have also voiced concern for women who recently married and have a name different from their birth certificate.

“This isn’t just about women who have changed their name, this is about any person who’s ever changed their name,” Karen Sicheneder with When She Votes said. “I think it’s disingenuous when you hear arguments that, ‘Well, everyone has an ID,’ no, they don’t.”

According to ABC, noncitizens voting in elections is uncommon. A 2024 audit of Georgia voter rolls found that out of 8.2 million registered voters, 20 non-citizens were registered to vote. Only nine ended up casting a ballot.

Lennon added that some invalid registrations also come from application mistakes.

“When people are filling out these forms, if they make a mistake, if they fill one out and they’re not supposed to or they think they’re supposed to, or they think that they’re eligible, those kinds of things do happen very rarely,” Lennon said. “But in an instance of actually voting, very, very uncommon.”

Lennon added that until the bill is passed, prospective voters should continue to head to the polls.

“We do have an April 7 election that’s coming up. We want people to get out and vote, make their voice heard, “Lennon said.

The Missouri House Special Committee on Redistricting is also hosting a public hearing on Wednesday at 4 p.m. in House Hearing Room 1 for House Concurrent Resolution 48. The bill voices the Missouri General Assembly’s support for the SAVE Act and urges the United States Senate to approve the bill.

Citizens can also submit testimonies for the hearing.

Click here to follow the original article.