Utah’s first-of-its-kind water reclamation facility transforms toilet water into water plants crave

CNN Newsource

Originally Published: 22 JAN 26 13:24 ET

By Chris Reed

Click here for updates on this story

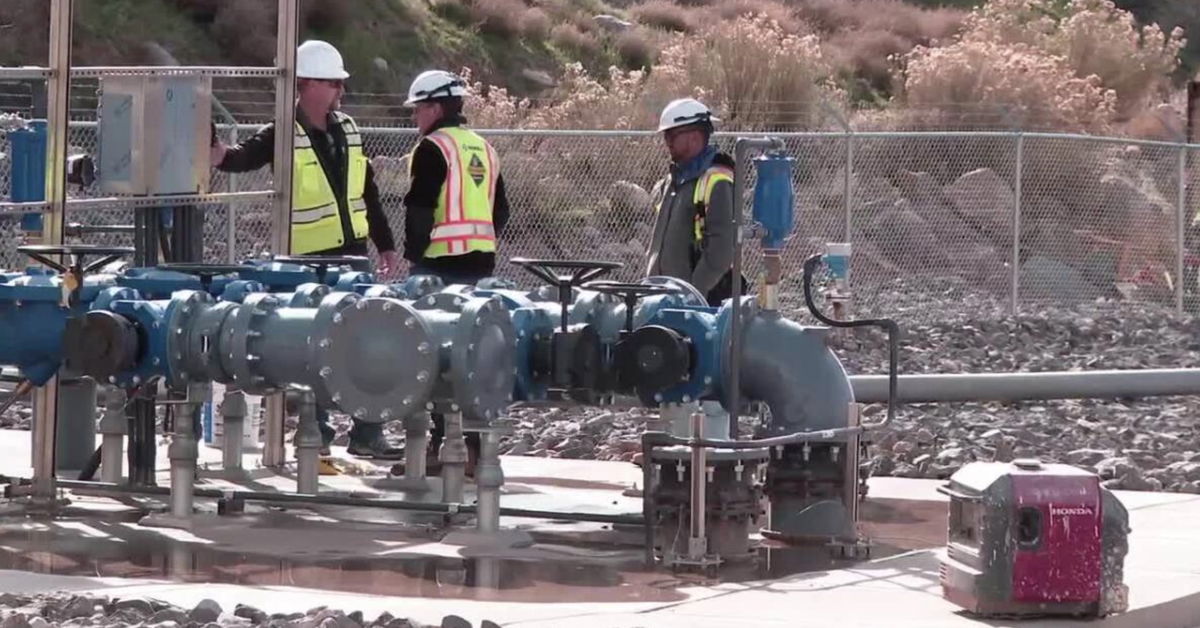

LA VERKIN, Utah (KSTU) — A groundbreaking $51 million water reclamation facility is about to transform how southern Utah handles wastewater. The Confluence Park Water Reclamation Facility represents 20 years of planning and construction, and it’s the first of its kind in Utah.

“As a child, I always wanted to be a marine biologist. But I also wanted to live here. So those two things don’t work together very well,” said Bradley Johnson, who grew up in Hurricane and La Verkin and now works at the facility.

Johnson said he never intends to leave the area because he loves the beauty of the terrain and landscapes. The 34-year-old is helping improve the water supply situation in Washington County through his work at this innovative facility.

All wastewater from public sewer systems in the Hurricane-LaVerkin-Toquerville area will be processed here. The facility may be hard to find — from the outside, it could easily be mistaken for a business park, Amazon warehouse or gymnasium.

“The least desirable thing next to a nuclear reactor is a wastewater treatment plant. So if we’re hitting well enough that you need additional directions, there’s a little bit of comfort for us,” said Mike Chandler, superintendent of Ash Creek Special Service District.

The facility uses new technology with a triple-filtering chemical and filtering system designed to prevent the characteristic bad odors typically associated with wastewater treatment plants. The project is being funded mostly through impact fees on new homes and development.

“Growth needs to pay for growth,” Chandler said.

The process begins when wastewater enters the collection system.

“A toilet is flushed. A sink is turned off. The dishwasher turns off. The water comes down through our collection system, conveyed to the front of our plant,” Chandler said.

The water that emerges meets Type 1 water standards according to state regulations — equivalent to pristine groundwater from a well. This treated water can be used to irrigate farms, parks, schools and home gardens.

“You’re able to pump this to the local elementary school. They can put it on their soccer fields. They can go to the local golf course. It can be used on residential gardens, and there’s not the likelihood or any chance of really there being any sort of contamination,” Chandler said.

The facility represents a significant component of the Washington County Water Conservancy District’s overall water reuse strategy. Chandler said the plant will help offset agriculture’s impact on the dwindling water supply in the region.

“That facility with the storage that it will allow increases the degree of robustness that we have as far as water scarcity through years like this, where there’s no snow on the mountains as you see out there today, which makes it a little bit problematic for us as we look and say, ‘What’s this next water year going to look like?'” Chandler said.

The Confluence Park facility uses technology developed in the Netherlands during the 1990s and 2000s, only licensed for use in the United States in 2016.

“So, relatively new process, first of its kind in Utah,” Chandler said.

The facility is currently undergoing final testing with clean water. Full wastewater processing will begin within the next week.

The biological process relies on bacteria to break down contaminants. Let the biologist who lives in LaVerkin explain.

“So the bacteria, they’ll eat the organic matter and contaminants, convert it into more of themselves through reproduction. And then we essentially just have to get rid of those bugs. And that’s through filtration,” Johnson said.

Johnson emphasized the quality of the final product.

“Essentially, the water that comes out of here is way cleaner, like way, way cleaner than the water that you see just in the Virgin River. And you’re willing to go play in that with your kids and stuff, so there shouldn’t be any concern with lawns being sprinklered with it or watering your garden,” Johnson said.

Please note: This story was provided to CNN Wire by an affiliate and does not contain original CNN reporting. This content carries a strict local market embargo. If you share the same market as the contributor of this article, you may not use it on any platform.

The-CNN-Wire™ & © 2026 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.

Senate Minority Leader Melissa Wintrow

Senate Minority Leader Melissa Wintrow House Minority Leader Ilana Rubel

House Minority Leader Ilana Rubel