Missouri’s primary care shortage is causing patients to put their health on hold

Gabrielle Teiner

Editor’s note: The timeline of incoming new hires has been clarified.

COLUMBIA, Mo. (KMIZ)

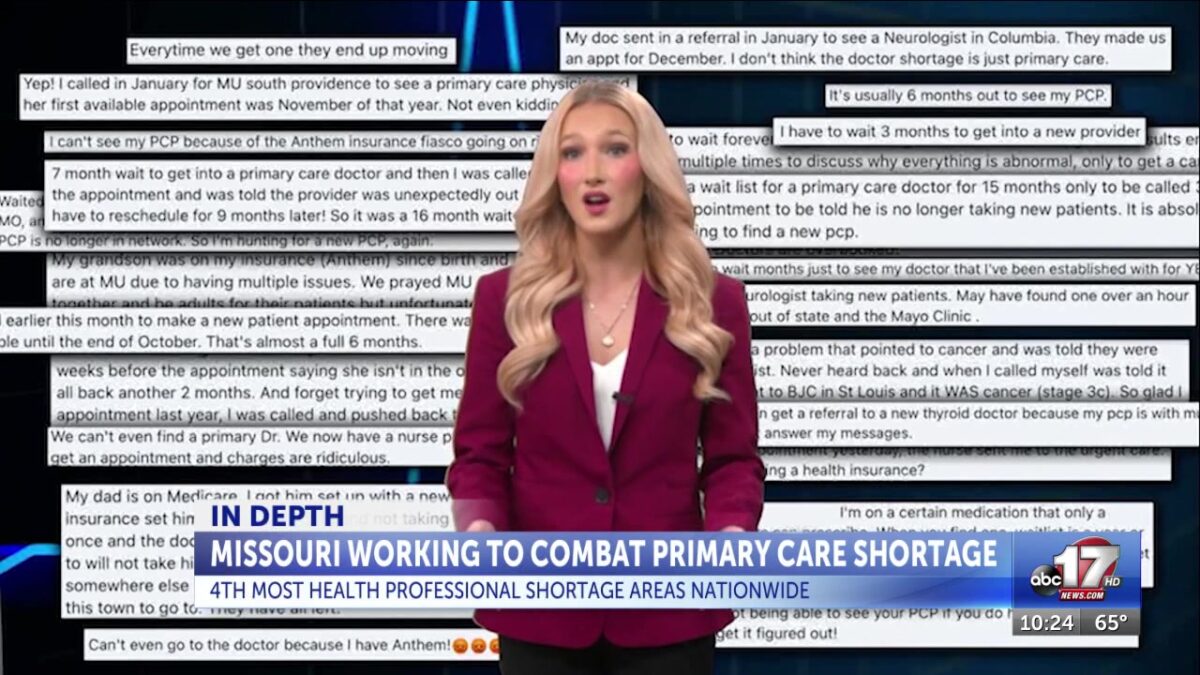

Finding a primary care doctor in Missouri is starting to feel like winning the lottery to some — rare, unpredictable and out of reach for many.

Seamus Levin, a Columbia resident, has been dealing with a diagnosis of sleep apnea for about a year and a half now. While figuring out his diagnosis, his primary care provider left, and ever since, his experience has been “frustrating,” “demoralizing” and “scary.”

He went to his primary care provider with Boone Health in March 2024. The provider suggested they do a sleep study, but didn’t have availability at the hospital to do that until July.

“The technician there actually said that I had one of the worst cases of central sleep apnea seen in anybody my age or younger, and that I need to be referred to a cardiologist and that my doctor should come with results two weeks later,” Levin said. “I still hadn’t received calls.”

The issues with establishing health care and costs have even gotten Levin thinking about moving to a different state, but the shortage isn’t just happening here in Missouri; it’s nationwide.

“We are struggling with primary care access, just like every state across the country,” said Dr. Heidi Miller, chief medical officer for the Department of Health and Senior Services. “This is a national problem, and in Missouri, we are absolutely 100% feeling it.”

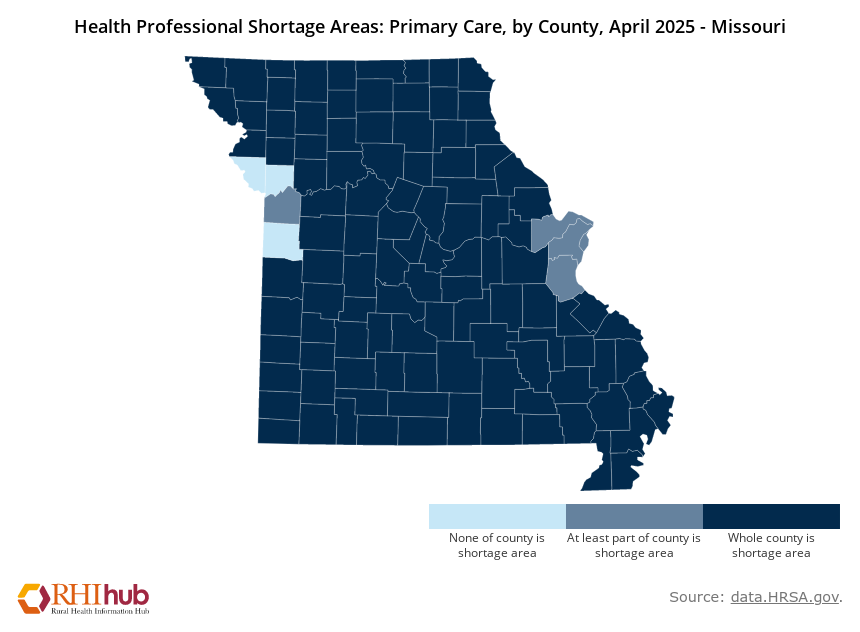

Almost every Missouri county — 111 out of 114 — is designated as a Health Professional Shortage Area, meaning there are not enough primary care, dental and mental health doctors to serve the population. This means only about 22.3% of health care needs are being addressed in those areas.

A HPSA is defined as a place with more than 3,500 patients per provider available. The ratio of doctors to patients depends on where you live, as there are a higher number of providers in more urban areas than rural areas.

“We estimate that it’s probably at least 2,200 patients per provider,” says Miller. “So in some areas that are those health professional shortage areas, the ratio is above 3,500 patients per provider, and in some of our rural areas is probably far more than that.”

Miller says a reasonably sized patient panel is about 1,500 patients per physician.

Running the health care gauntlet

Levin calls the clinic. He gets told someone will call him back later. Three weeks go by, and no return call from the clinic.

He calls again. They now say he needs to be assigned to a new primary care physician, but that can’t happen until March, a year after he initially went to the doctor for his breathing problems.

“We’re in Columbia. We have a hundred thousand-some-odd people… You’re telling me that I can’t find a doctor until March because we just don’t have enough here?” Levin told ABC 17 News.

And waiting so long cost him about $500 because he had maxed out on his insurance.

Levin says if he needs to see a doctor at a convenient-care clinic, it’s harder to advocate for himself because they don’t know his history.

“I don’t have anybody that really knows me, that knows my history, knows kind of my preferences and my choices, so that’s been one of those things, it’s like, okay, I’m kind of hosed if I need to go get a treatment plan, it’s going to be months before someone else can see me,” said Levin.

Levin hasn’t seen a primary care doctor since the summer of 2024 — a familiar tune to many Mid-Missourians.

“When I started here, I don’t know how many patients would ask me now, ‘Are you sticking around? Are you planning to leave? How long are you going to be here?’ Because they just didn’t really want to, you know, start all over,” said Dr. Whitney LeFevre, assistant professor of family and community medicine and director of the Rural Scholars Medical Program at the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

Even though Levin is on a BiPAP machine while he sleeps, he feels like he’s not getting any better.

“Nobody is really monitoring my BiPAP as far as I can tell,” said Levin. “I get calls to say the results are great, but I don’t feel any different. There have been a few times where I was like, I’m not going to wear it tonight because it’s not making a difference.”

Missouri missing key ‘players’

According to HRSA’s quarterly summary report, Missouri needs 476 primary care physicians to remove the state’s primary care HPSA designations.

“You can equate some of the shortages that we are experiencing with primary care, similar to you don’t have someone on your team, you don’t want to take the field or take the court without them, that important team player,” said Joni Adamson, who is with the Missouri Primary Care Association. “It’s really a ripple effect when we don’t have all of the team there when it’s needed.”

Adamson says having continuous care can lead to better health outcomes, reduced hospital admissions, fewer trips to the emergency room and better management of chronic diseases.

Multiple factors contribute to the primary care shortage, like physician burnout, aging workforce, low pay and financial burdens.

Researchers say 32% of Missouri’s primary care physicians are retirement age, and by 2030, 1-in-5 Missourians will be older than 65 years old.

“Many of our doctors are feeling the stress of administrative burnout, and so that can make people work less than full time to make their job more doable, and that can decrease access to patients,” said Dr. Natalie Long, who is the president of the Missouri Academy of Family Physicians.

Miller says doctors often need to spend time outside their work hours filling out paperwork, working on charts, etc., and in turn, step away from the office to cope with it.

“I have many peer physicians who work maybe 80% of the time, or they’re paid 80% of the time, and that still ends up filling, 60, 70 hours per week, so if our physicians are not scheduled for clinic 40 hours a week, then our physician shortage is likely even worse than what the national and state statistics are telling us,” Miller said.

Too few landing spots

Arguably, the biggest factor contributing to the primary care shortage is not having enough residency opportunities for freshly graduated medical students.

Missouri has seven medical schools, ranking ninth in the country for generating medical school graduates. Once a medical student graduates, they need to do graduate medical education, also known as a residency. Too few are offered in Missouri.

“We graduate a lot of medical school graduates, about a thousand per year from our own state, but we only have about 700 resident slots,” Miller said. “Even if they stayed in-state and other folks didn’t come into the state, we would still automatically be exporting over 300 of our own medical school graduates.”

While the problem persists, there are plans in progress to help address the shortage.

Miller says a long-term strategic plan has been created to build graduate medical education and create more residency slots in specialties needed the most, like primary care.

In 2023, the Missouri Legislature passed HB 1162, which requires DHSS to establish a graduate medical education grant program that awards grants to universities operating medical education programs to fund 20 residency spots each fiscal year, starting in 2024 and ending in 2034.

The bill also created the Graduate Medical Education Grant Program Fund, with money appropriated from the General Assembly. This funds the Graduate Medical Education Technical Assistance Center, which will serve as a hub to support current residency programs and build additional ones.

The bill also increases residency programs that do not already have them, funds and strengthens existing programs, funds expansion opportunities, funds rural and addiction training into existing programs and supports universities already offering residency to increase their offerings.

Most residency programs are covered by Medicare, but rules set nearly 30 years ago limit the number of reimbursements residency programs can receive from the federal government.

“There are many institutions, facilities across the state where they’re strapped or they want to train the next generation, but they don’t have any additional federal funding to do so,” Miller said.

When deciding who gets the funding, lawmakers and health officials focused on the highest need areas, like primary care, family medicine, OBGYN, psychiatry and pediatrics.

Miller said since the program launched, 25 residents are now training to become future doctors. But, they didn’t want to stop there.

“We realized that the most cost-effective, long-term, impactful intervention would be to actually develop brand new programs or to encourage current programs to do major expansions to rural hospitals,” Miller said. “The goal is for us to ultimately generate dozens and dozens of additional new slots that continue to produce new physicians each year.”

According to HRSA, only 2% of residency training occurs in rural areas, so the fund provides money to create new residency programs in those areas, awarding $750,000 per grant. From 2008 to 2024, residency training programs in rural or health center settings has doubled across the country. Bothwell Regional Health Center in Sedalia has a new family medicine program because of this grant.

DHSS offers the Health Professional Loan Repayment Program, which gives money to doctors to pay off their student loans and other medical education expenses. In order to receive money to pay off loans, a medical student must practice for two years in an area of need, which is defined by DHSS.

MU Health Care also has its Rural Scholars Program, run by LeFevre, which encourages MU School of Medicine graduates who have ties to rural Missouri to train and practice there, which she says has been successful.

“Through grant funding, we’ve been able to offer significant chunks of scholarship to our rural students in our Rural Scholars Program,” LeFevre said. “Students have said to us, ‘I’ve decided to be a pediatrician now because I’m not as worried about the finances after I leave here.'”

LeFevre says there can be a number of reasons why a medical school graduate may look outside the state for residency. Those may be Missouri not having a specialty they want, personal and family reasons and more. Doctors may also match outside of the state based on the results of their Resident Matching, which uses an algorithm to place applicants into residency programs and fellowship positions.

Recruitment continues

But looming cuts at the federal level could put a pause on this momentum.

“Funding, we are all worried about,” Adamson said. “We’re always looking to diversify ways that funding may come in for creating partnerships that, you know, maybe there’s avenues out there that we haven’t explored that would help create financial opportunities for partnerships to invest in health care and advocating for what we have and maintaining that.”

Long agrees and thinks Missouri needs to invest in primary care because the outcomes show results.

“The outcomes show that patients have longer lifespans, they have overall health that’s improved and we are reducing the overall cost of health care,” Long said. “Those are great things that we should continue to invest in.”

LeFevre worries potential cuts to health care could wipe away all the progress the program has made.

“It’s really disappointing to think of all the wonderful things that we’ve been able to do and if that money goes away, what kinds of decisions we’re going to have to make,” LeFevre said.

MU Health Care, Boone Health and SSM Health St. Mary’s say new primary care providers will be starting soon.

In an email to ABC 17 News, a spokesperson for SSM Health St. Mary’s says several more primary care providers will start in the next few weeks. As of May, the average time to get into established care with a provider was 33 days. SSM’s goal is to get patients in to see a doctor in two weeks.

Boone Health says establishing primary care is getting faster, but patients still will have to wait a few weeks to get in. In an email to ABC 17 News, Boone Health is able to make appointments for later this month or early to mid-July, so between three and five weeks. Boone Health has hired five primary care providers since Jan. 1, with one starting on Tuesday. As many as four more will be joining Boone Health before the end of the year, with each new provider able to take between 1,500-1,800 new patients.

MU Health Care could not provide a number of providers hired in the last year, but said 13 new providers are starting throughout next fiscal year in family medicine, pediatrics, OB/GYN and internal medicine. The next fiscal year begins in July.