Non-profit investigation outlines 7 reforms to address unchecked sex abuse in Idaho prisons

InvestigateWest

Independent oversight, policy changes in other states show steps to protect Idaho inmates at risk of victimization

Editor’s note: “Guarded by Predators” is an investigative series exposing rape and abuse by Idaho’s prison guards and the system that shields them. Find the entire series at investigatewest.org/guarded-by-predators.

Originally Published: Nov. 20, 2025

By Whitney Bryen / InvestigateWest

BOISE, Idaho — Dozens of Idaho inmates have suffered unchecked sexual abuse by women’s prison guards and faced retaliation when they spoke up. As Idaho officials promise to review problematic policies and accusations revealed by InvestigateWest, other states offer ideas for increased transparency and reform.

During a yearlong investigation, current and formerly incarcerated women told InvestigateWest how they were raped in janitor’s closets, employee offices and at work sites where cameras couldn’t see. They said guards exploited closed-door disciplinary hearings to coerce sexual favors. Some women refused to file reports against the correction officers who harassed, groped and assaulted them for fear that they would be written up, placed in segregated housing, or chastised by other inmates and staff. And when they did speak up, their complaints were frequently ignored and investigations were sloppy.

The Department of Correction rarely referred cases to law enforcement for criminal investigation, keeping most allegations hidden from the public. Since 2015, at least 18 guards accused of sexual misconduct were allowed to quietly resign, leaving their employment records clean and enabling them to take jobs at facilities in other states.

Idaho is not alone in grappling with widespread sexual abuse by prison staff. One of the biggest challenges to addressing this nationwide crisis is the “iron curtain” that protects prisons from independent and public scrutiny, said Michele Deitch, who runs the National Resource Center for Correctional Oversight.

“When an institution has total control over people’s lives, abuse can happen,” Deitch said. “Independent oversight is critical as a way to alert the public to what’s going on inside and provide a vehicle for people inside to share their concerns about what’s happening to them.”

We looked at efforts in other states to improve transparency and accountability for incarcerated victims of sexual abuse and violence, including an Arizona governor’s executive order and a decade-old settlement in Washington.

Problem: Idaho’s rape law is ‘very narrow’

Reform: Expand the criminal definition of sexual assault when the victim is in custody

Idaho limits its definition of sexual assault when the victim is an inmate. Even though federal standards say all inappropriate touching by prison workers and even suggestive comments or voyeurism are illegal, Idaho’s law protects inmates from abuse only when staff touch the victim’s genitals or they’re made to touch the genitals of staff.

Brenda Smith, director of the Project on Addressing Prison Rape at American University, said Idaho’s law is “very narrow” and could leave the state liable.

State laws that closely align with federal standards protecting inmates from rape, sexual assault, coercion and harassment by prison staff make it easier for prosecutors to hold abusers accountable. Idaho lawmakers could amend the current law or pass new ones that more closely mimic federal guidance.

Brenda Smith is the director of the Project on Addressing Prison Rape at American University in Washington, D.C., and has studied the federal standards and state laws designed to protect inmates from sexual abuse. She says Idaho’s law is ”very narrow” compared to other states and could leave the state liable. (Provided by American University Washington College of Law)

Brenda Smith is the director of the Project on Addressing Prison Rape at American University in Washington, D.C., and has studied the federal standards and state laws designed to protect inmates from sexual abuse. She says Idaho’s law is ”very narrow” compared to other states and could leave the state liable. (Provided by American University Washington College of Law)

Since 2015, only three Idaho women’s prison guards have been charged with sexual contact with a prisoner, InvestigateWest found.

Arizona and Nevada allow prosecutors to charge guards and other correction workers for coercion and harassment, in addition to rape and sexual assault. In Arizona, guards can be charged for attempting or requesting sexual contact or exposing their private areas to inmates, which includes the inner thighs, breasts and buttocks that aren’t covered by Idaho’s law.

Oregon and Washington have felony laws similar to Idaho’s, but also have laws with reduced punishments that allow prosecutors to charge guards for less severe abuse of an inmate.

Problem: Camera blind spots enable abuse

Reform: Increase visibility in high-risk areas

Following a 2007 lawsuit filed by women alleging sexual assault by guards, Washington state’s Department of Corrections installed additional security cameras in high-risk areas, limited guards’ access to those areas and added viewing windows to rooms where sexual misconduct had been reported. The settlement also required prisons, inmate work sites and community custody facilities to implement new training and procedures for responding to misconduct.

In a statement from the inmates’ attorneys announcing the settlement, lawyer Beth Colgan said the changes “have made the prisons a safer place so that women in Washington do not have to experience the horror of being locked up with and unable to escape their abusers.”

Problem: Investigations lack independence

Reform: Designate a corrections ombudsman who inmates can contact

A growing number of states are using corrections ombudsmen to increase independent oversight of the prison system and provide additional protection for inmates, including those reporting sexual abuse by guards.

Idaho inmates have several options for how to file a report alleging sexual abuse by staff. However, each option leads to an employee of the Department of Correction, often a co-worker or supervisor of the person being accused. Inmates are unable to report abuse directly to police, leaving it up to the prison system to notify law enforcement of potential crimes. But that rarely happens, InvestigateWest found.

Thursday July 24, 2025: Andrea Weiskircher is pictured outside of the Ada County Courthouse in Boise, Idaho. Weiskircheron was on her way to drug court. Weiskircheron is currently on parole for Grand Theft by Any Common Law Larceny, Embezzlement, Extortion or Receiving Stolen Goods, etc. and on probation for burglary. Kyle Green/InvestigateWest

Thursday July 24, 2025: Andrea Weiskircher is pictured outside of the Ada County Courthouse in Boise, Idaho. Weiskircheron was on her way to drug court. Weiskircheron is currently on parole for Grand Theft by Any Common Law Larceny, Embezzlement, Extortion or Receiving Stolen Goods, etc. and on probation for burglary. Kyle Green/InvestigateWest

Corrections ombudsmen in Washington, Oregon, Texas and New Jersey operate independently of the prison system, but unlike law enforcement, inmates can contact them directly, and the ombudsmen have access to prison files including abuse allegations and investigations. They identify gaps in procedure, help inmates and their families understand their rights, and investigate complaints.

Washington’s Office of the Ombuds has a budget of $2.5 million and 15 staff, while Oregon spends less than $400,000 on one ombudsman. Both offices report directly to the governor.

Last year, Idaho lawmakers created a similar statewide office to monitor youth treatment facilities after InvestigateWest uncovered years of child abuse and neglect that was met with little to no punishment from state regulators. Lawmakers established the Health and Social Services ombudsman to ensure youth facilities comply with state rules. In September, the ombudsman reported to lawmakers that the state still isn’t penalizing facilities where kids could be at risk.

Problem: Limited oversight

Reform: Require state-level inspections

News reports of sexual abuse against inmates across the country have led to increased public scrutiny of prisons nationwide.

National standards require prisons to be audited at least every three years to ensure they’re following policies designed to prevent and respond to sexual abuse. Auditors are chosen and paid by the prison system they’re inspecting. InvestigateWest reviewed the most recent audits of all three Idaho women’s prisons and found that auditors recorded discrepancies but passed the prisons as “in compliance” anyway. Even when facilities are marked as noncompliant, enforcement is limited.

Some states require prisons to undergo state-level inspections to ensure the safety of people in custody. Following reports of sexual abuse against Arizona inmates and beatings of staff, an executive order by Gov. Katie Hobbs established a committee of lawmakers, advocates, former inmates and people with corrections experience to inspect state facilities. Inspectors assess prison conditions and safety protocols, including the inmate grievance process and how long it takes staff to respond.

Department of Correction Director Bree Derrick has not responded to questions about what the agency is doing to ensure the safety of women in custody since InvestigateWest’s findings were released. (Provided)

Department of Correction Director Bree Derrick has not responded to questions about what the agency is doing to ensure the safety of women in custody since InvestigateWest’s findings were released. (Provided)

In New Jersey, Washington and Minnesota, lawmakers created a corrections ombudsman’s office that performs regular inspections of state prisons in addition to investigating complaints from inmates. Deitch, whose corrections oversight project published a list of independent supervision models in each state and model legislation, said several states are adopting this model.

“States that have had the best success with independent oversight is when it comes out of a non-adversarial approach rather than waiting for a lawsuit to require it,” Deitch said. “It’s when the Department of Correction sees the benefit to them also that we all benefit from that collaboration.”

Idaho does not require state-level inspections of prisons or jails.

Problem: Victims lack support and access to counseling

Reform: Partner with nonprofits and victim advocates who provide medical, legal and emotional support to inmates victimized behind bars

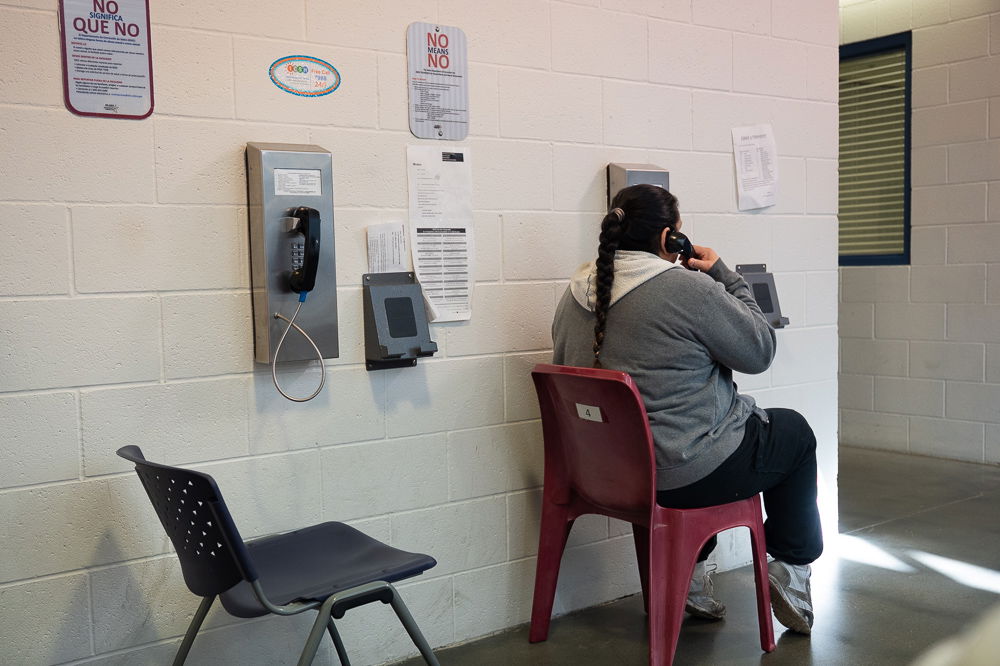

Most prison staff are not trained to provide counseling to victims of sexual abuse, leaving inmates to suffer in silence. Restrictions and costly fees associated with making phone or video calls from prison make it difficult for victims to access resources after they experience harassment or assault. Some women who told InvestigateWest they experienced sexual abuse in Idaho prisons said they requested mental health treatment from a provider who does not work for the prison system because they feared retaliation. But they were denied.

Prisons in South Carolina, Washington and Texas partner with victim service agencies to fill those gaps in inmate care. Some prisons provide office space for rape crisis counselors to meet with inmates. Those partnerships allow advocates to accompany victims to forensic exams and operate confidential hotlines that are free to call and accessible from prison phones. And they help victims navigate law enforcement investigations and charges.

Problem: Victims face retaliation and isolation

Reform: Limit segregated housing, closely monitor victims of abuse

Idaho women’s prison guards accused of preying on inmates faced few consequences, InvestigateWest found. But the women who spoke up say they were the ones punished. Reporting sexual abuse can mean that victims get moved away from fellow inmates and into restrictive housing for their safety. Women described that as the “hole” — small cells where prisoners are confined up to 23 hours a day, like a maximum-security prison.

The outside of the women’s facility at the South Idaho Correctional Institution outside of Boise, ID. (Whitney Bryen/InvestigateWest)

The outside of the women’s facility at the South Idaho Correctional Institution outside of Boise, ID. (Whitney Bryen/InvestigateWest)

Placing inmates in solitary confinement after they report sexual abuse “may significantly suppress reporting at the facility,” according to a guide from the National Prison Rape Elimination Act Resource Center. The 10-year-old report from the center that sets national standards for preventing and responding to prison rape encourages prisons nationwide to avoid isolating inmates at risk of sexual abuse.

In one Pennsylvania prison, victims are placed in standard housing units without roommates or moved to an area where it’s easier for staff to monitor them. The Segregation Reduction Project, an initiative by the nonprofit Vera Institute that works with prisons to reduce use of isolation, called it a model for other states.

In Oregon, case managers trained in sexual assault response meet regularly with at-risk inmates to address any safety concerns.

Problem: Staff exploit private disciplinary hearings

Reform: Allow inmates to have a representative present in disciplinary hearings

After an inmate is written up for violating a rule in Idaho prisons, a disciplinary hearing offers the inmate a chance to respond to the accusation. A correction officer presides over the hearing and either dismisses the write-up or imposes sanctions such as solitary confinement or commissary restrictions. Those hearings are conducted behind closed doors, out of sight of security cameras, usually by a sergeant with no other witnesses. Department of Correction policy allows inmates to request a hearing assistant — a prison worker who has been trained to help inmates through the disciplinary process — but only if the inmate is unable to gather evidence or understand the proceeding.

Multiple women told InvestigateWest that officers used these hearings to offer leniency in exchange for sexual favors. The Department of Correction said it was only aware of “one complaint of this nature.”

In 2021, New York passed the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement Act allowing inmates to have a representative present during disciplinary hearings in order to reduce their risk of exploitation. Representatives can include an attorney, paralegal, law student or another incarcerated person. In a statement supporting the law, the nonprofit We the Action that connects attorneys with people who need representation wrote: “Having representation can help beat those charges and attempts, and help ensure that people are treated more humanely and fairly.”

Idaho lawmakers could pass a similar law. Or, the Department of Correction could change its policy to permit inmates to have a representative present at hearings.

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Reporter Whitney Bryen covers injustice and vulnerable populations, including mental health care, homelessness and incarceration. Reach her at 208-918-2458, whitney@invw.org and on X @WhitneyBryen.